【转载】Async IO in Python: A Complete Walkthrough

Async IO is a concurrent programming design that has received dedicated support in Python, evolving rapidly from Python 3.4 through 3.7, and probably beyond.

You may be thinking with dread, “Concurrency, parallelism, threading, multiprocessing. That’s a lot to grasp already. Where does async IO fit in?”

This tutorial is built to help you answer that question, giving you a firmer grasp of Python’s approach to async IO.

Here’s what you’ll cover:

- Asynchronous IO (async IO): a language-agnostic paradigm (model) that has implementations across a host of programming languages

async/await: two new Python keywords that are used to define coroutinesasyncio: the Python package that provides a foundation and API for running and managing coroutines

Coroutines (specialized generator functions) are the heart of async IO in Python, and we’ll dive into them later on.

Note: In this article, I use the term async IO to denote the language-agnostic design of asynchronous IO, while

asynciorefers to the Python package.

Before you get started, you’ll need to make sure you’re set up to use asyncio and other libraries found in this tutorial.

Setting Up Your Environment

You’ll need Python 3.7 or above to follow this article in its entirety, as well as the aiohttp and aiofiles packages:

1

2

3

$ python3.7 -m venv ./py37async

$ source ./py37async/bin/activate # Windows: .\py37async\Scripts\activate.bat

$ pip install --upgrade pip aiohttp aiofiles # Optional: aiodns

For help with installing Python 3.7 and setting up a virtual environment, check out Python 3 Installation & Setup Guide or Virtual Environments Primer.

With that, let’s jump in.

The 10,000-Foot View of Async IO

Async IO is a bit lesser known than its tried-and-true cousins, multiprocessing and threading. This section will give you a fuller picture of what async IO is and how it fits into its surrounding landscape.

Where Does Async IO Fit In?

Concurrency and parallelism are expansive subjects that are not easy to wade into. While this article focuses on async IO and its implementation in Python, it’s worth taking a minute to compare async IO to its counterparts in order to have context about how async IO fits into the larger, sometimes dizzying puzzle.

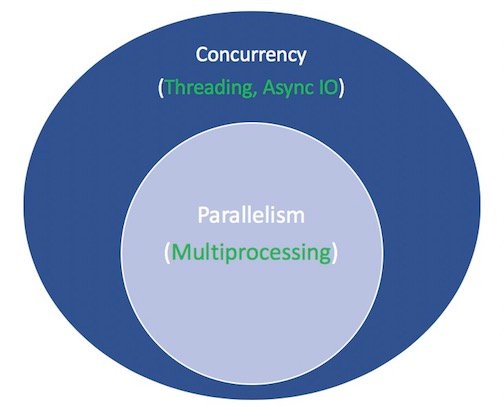

Parallelism consists of performing multiple operations at the same time. Multiprocessing is a means to effect parallelism, and it entails spreading tasks over a computer’s central processing units (CPUs, or cores). Multiprocessing is well-suited for CPU-bound tasks: tightly bound

forloops and mathematical computations usually fall into this category.Concurrency is a slightly broader term than parallelism. It suggests that multiple tasks have the ability to run in an overlapping manner. (There’s a saying that concurrency does not imply parallelism.)

Threading is a concurrent execution model whereby multiple threads take turns executing tasks. One process can contain multiple threads. Python has a complicated relationship with threading thanks to its GIL, but that’s beyond the scope of this article.

What’s important to know about threading is that it’s better for IO-bound tasks. While a CPU-bound task is characterized by the computer’s cores continually working hard from start to finish, an IO-bound job is dominated by a lot of waiting on input/output to complete.

To recap the above, concurrency encompasses both multiprocessing (ideal for CPU-bound tasks) and threading (suited for IO-bound tasks). Multiprocessing is a form of parallelism, with parallelism being a specific type (subset) of concurrency. The Python standard library has offered longstanding support for both of these through its multiprocessing, threading, and concurrent.futures packages.

Now it’s time to bring a new member to the mix. Over the last few years, a separate design has been more comprehensively built into CPython: asynchronous IO, enabled through the standard library’s asyncio package and the new async and await language keywords. To be clear, async IO is not a newly invented concept, and it has existed or is being built into other languages and runtime environments, such as Go, C#, or Scala.

The asyncio package is billed by the Python documentation as a library to write concurrent code. However, async IO is not threading, nor is it multiprocessing. It is not built on top of either of these.

In fact, **async IO is a single-threaded, single-process design**: it uses cooperative multitasking, a term that you’ll flesh out by the end of this tutorial. It has been said in other words that async IO gives a feeling of concurrency despite using a single thread in a single process. Coroutines (a central feature of async IO) can be scheduled concurrently, but they are not inherently concurrent.

To reiterate, async IO is a style of concurrent programming, but it is not parallelism. It’s more closely aligned with threading than with multiprocessing but is very much distinct from both of these and is a standalone member in concurrency’s bag of tricks.

That leaves one more term. What does it mean for something to be asynchronous? This isn’t a rigorous definition, but for our purposes here, I can think of two properties:

- Asynchronous routines are able to “pause” while waiting on their ultimate result and let other routines run in the meantime.

- Asynchronous code, through the mechanism above, facilitates concurrent execution. To put it differently, asynchronous code gives the look and feel of concurrency.

Here’s a diagram to put it all together. The white terms represent concepts, and the green terms represent ways in which they are implemented or effected:

I’ll stop there on the comparisons between concurrent programming models. This tutorial is focused on the subcomponent that is async IO, how to use it, and the APIs that have sprung up around it. For a thorough exploration of threading versus multiprocessing versus async IO, pause here and check out Jim Anderson’s overview of concurrency in Python. Jim is way funnier than me and has sat in more meetings than me, to boot.

Async IO Explained

Async IO may at first seem counterintuitive and paradoxical. How does something that facilitates concurrent code use a single thread and a single CPU core? I’ve never been very good at conjuring up examples, so I’d like to paraphrase one from Miguel Grinberg’s 2017 PyCon talk, which explains everything quite beautifully:

Chess master Judit Polgár hosts a chess exhibition in which she plays multiple amateur players. She has two ways of conducting the exhibition: synchronously and asynchronously.

Assumptions:

- 24 opponents

- Judit makes each chess move in 5 seconds

- Opponents each take 55 seconds to make a move

- Games average 30 pair-moves (60 moves total)

Synchronous version: Judit plays one game at a time, never two at the same time, until the game is complete. Each game takes (55 + 5) * 30 == 1800 seconds, or 30 minutes. The entire exhibition takes 24 * 30 == 720 minutes, or 12 hours.

Asynchronous version: Judit moves from table to table, making one move at each table. She leaves the table and lets the opponent make their next move during the wait time. One move on all 24 games takes Judit 24 * 5 == 120 seconds, or 2 minutes. The entire exhibition is now cut down to 120 * 30 == 3600 seconds, or just 1 hour. (Source)

There is only one Judit Polgár, who has only two hands and makes only one move at a time by herself. But playing asynchronously cuts the exhibition time down from 12 hours to one. So, cooperative multitasking is a fancy way of saying that a program’s event loop (more on that later) communicates with multiple tasks to let each take turns running at the optimal time.

Async IO takes long waiting periods in which functions would otherwise be blocking and allows other functions to run during that downtime. (A function that blocks effectively forbids others from running from the time that it starts until the time that it returns.)

Async IO Is Not Easy

I’ve heard it said, “Use async IO when you can; use threading when you must.” The truth is that building durable multithreaded code can be hard and error-prone. Async IO avoids some of the potential speedbumps that you might otherwise encounter with a threaded design.

But that’s not to say that async IO in Python is easy. Be warned: when you venture a bit below the surface level, async programming can be difficult too! Python’s async model is built around concepts such as callbacks, events, transports, protocols, and futures—just the terminology can be intimidating. The fact that its API has been changing continually makes it no easier.

Luckily, asyncio has matured to a point where most of its features are no longer provisional, while its documentation has received a huge overhaul and some quality resources on the subject are starting to emerge as well.

The asyncio Package and async/await

Now that you have some background on async IO as a design, let’s explore Python’s implementation. Python’s asyncio package (introduced in Python 3.4) and its two keywords, async and await, serve different purposes but come together to help you declare, build, execute, and manage asynchronous code.

The async/await Syntax and Native Coroutines

A Word of Caution: Be careful what you read out there on the Internet. Python’s async IO API has evolved rapidly from Python 3.4 to Python 3.7. Some old patterns are no longer used, and some things that were at first disallowed are now allowed through new introductions.

At the heart of async IO are coroutines. A coroutine is a specialized version of a Python generator function. Let’s start with a baseline definition and then build off of it as you progress here: a coroutine is a function that can suspend its execution before reaching return, and it can indirectly pass control to another coroutine for some time.

Later, you’ll dive a lot deeper into how exactly the traditional generator is repurposed into a coroutine. For now, the easiest way to pick up how coroutines work is to start making some.

Let’s take the immersive approach and write some async IO code. This short program is the Hello World of async IO but goes a long way towards illustrating its core functionality:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# countasync.py

import asyncio

async def count():

print("One")

await asyncio.sleep(1)

print("Two")

async def main():

await asyncio.gather(count(), count(), count())

if __name__ == "__main__":

import time

s = time.perf_counter()

asyncio.run(main())

elapsed = time.perf_counter() - s

print(f"{__file__} executed in {elapsed:0.2f} seconds.")

When you execute this file, take note of what looks different than if you were to define the functions with just def and time.sleep():

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

$ python3 countasync.py

One

One

One

Two

Two

Two

countasync.py executed in 1.01 seconds.

The order of this output is the heart of async IO. Talking to each of the calls to count() is a single event loop, or coordinator. When each task reaches await asyncio.sleep(1), the function yells up to the event loop and gives control back to it, saying, “I’m going to be sleeping for 1 second. Go ahead and let something else meaningful be done in the meantime.”

Contrast this to the synchronous version:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# countsync.py

import time

def count():

print("One")

time.sleep(1)

print("Two")

def main():

for _ in range(3):

count()

if __name__ == "__main__":

s = time.perf_counter()

main()

elapsed = time.perf_counter() - s

print(f"{__file__} executed in {elapsed:0.2f} seconds.")

When executed, there is a slight but critical change in order and execution time:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

$ python3 countsync.py

One

Two

One

Two

One

Two

countsync.py executed in 3.01 seconds.

While using time.sleep() and asyncio.sleep() may seem banal, they are used as stand-ins for any time-intensive processes that involve wait time. (The most mundane thing you can wait on is a sleep() call that does basically nothing.) That is, time.sleep() can represent any time-consuming blocking function call, while asyncio.sleep() is used to stand in for a non-blocking call (but one that also takes some time to complete).

As you’ll see in the next section, the benefit of awaiting something, including asyncio.sleep(), is that the surrounding function can temporarily cede control to another function that’s more readily able to do something immediately. In contrast, `time.sleep()` or any other blocking call is incompatible with asynchronous Python code, because it will stop everything in its tracks for the duration of the sleep time.

The Rules of Async IO

At this point, a more formal definition of async, await, and the coroutine functions that they create are in order. This section is a little dense, but getting a hold of async/await is instrumental, so come back to this if you need to:

- The syntax

async defintroduces either a native coroutine or an asynchronous generator. The expressionsasync withandasync forare also valid, and you’ll see them later on. - The keyword

awaitpasses function control back to the event loop. (It suspends the execution of the surrounding coroutine.) If Python encounters anawait f()expression in the scope ofg(), this is howawaittells the event loop, “Suspend execution ofg()until whatever I’m waiting on—the result off()—is returned. In the meantime, go let something else run.”

In code, that second bullet point looks roughly like this:

1

2

3

4

async def g():

# Pause here and come back to g() when f() is ready

r = await f()

return r

There’s also a strict set of rules around when and how you can and cannot use async/await. These can be handy whether you are still picking up the syntax or already have exposure to using async/await:

- A function that you introduce with

async defis a coroutine. It may useawait,return, oryield, but all of these are optional. Declaringasync def noop(): passis valid:- Using

awaitand/orreturncreates a coroutine function. To call a coroutine function, you mustawaitit to get its results. - It is less common (and only recently legal in Python) to use

yieldin anasync defblock. This creates an asynchronous generator, which you iterate over withasync for. Forget about async generators for the time being and focus on getting down the syntax for coroutine functions, which useawaitand/orreturn. - Anything defined with

async defmay not useyield from, which will raise aSyntaxError.

- Using

- Just like it’s a

SyntaxErrorto useyieldoutside of adeffunction, it is aSyntaxErrorto useawaitoutside of anasync defcoroutine. You can only useawaitin the body of coroutines.

Here are some terse examples meant to summarize the above few rules:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

async def f(x):

y = await z(x) # OK - `await` and `return` allowed in coroutines

return y

async def g(x):

yield x # OK - this is an async generator

async def m(x):

yield from gen(x) # No - SyntaxError

def m(x):

y = await z(x) # Still no - SyntaxError (no `async def` here)

return y

Finally, when you use await f(), it’s required that f() be an object that is awaitable. Well, that’s not very helpful, is it? For now, just know that an awaitable object is either (1) another coroutine or (2) an object defining an .__await__() dunder method that returns an iterator. If you’re writing a program, for the large majority of purposes, you should only need to worry about case #1.

That brings us to one more technical distinction that you may see pop up: an older way of marking a function as a coroutine is to decorate a normal def function with @asyncio.coroutine. The result is a generator-based coroutine. This construction has been outdated since the async/await syntax was put in place in Python 3.5.

These two coroutines are essentially equivalent (both are awaitable), but the first is generator-based, while the second is a native coroutine:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

import asyncio

@asyncio.coroutine

def py34_coro():

"""Generator-based coroutine, older syntax"""

yield from stuff()

async def py35_coro():

"""Native coroutine, modern syntax"""

await stuff()

If you’re writing any code yourself, prefer native coroutines for the sake of being explicit rather than implicit. Generator-based coroutines will be removed in Python 3.10.

Towards the latter half of this tutorial, we’ll touch on generator-based coroutines for explanation’s sake only. The reason that async/await were introduced is to make coroutines a standalone feature of Python that can be easily differentiated from a normal generator function, thus reducing ambiguity.

Don’t get bogged down in generator-based coroutines, which have been deliberately outdated by async/await. They have their own small set of rules (for instance, await cannot be used in a generator-based coroutine) that are largely irrelevant if you stick to the async/await syntax.

Without further ado, let’s take on a few more involved examples.

Here’s one example of how async IO cuts down on wait time: given a coroutine makerandom() that keeps producing random integers in the range [0, 10], until one of them exceeds a threshold, you want to let multiple calls of this coroutine not need to wait for each other to complete in succession. You can largely follow the patterns from the two scripts above, with slight changes:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# rand.py

import asyncio

import random

# ANSI colors

c = (

"\033[0m", # End of color

"\033[36m", # Cyan

"\033[91m", # Red

"\033[35m", # Magenta

)

async def makerandom(idx: int, threshold: int = 6) -> int:

print(c[idx + 1] + f"Initiated makerandom({idx}).")

i = random.randint(0, 10)

while i <= threshold:

print(c[idx + 1] + f"makerandom({idx}) == {i} too low; retrying.")

await asyncio.sleep(idx + 1)

i = random.randint(0, 10)

print(c[idx + 1] + f"---> Finished: makerandom({idx}) == {i}" + c[0])

return i

async def main():

res = await asyncio.gather(*(makerandom(i, 10 - i - 1) for i in range(3)))

return res

if __name__ == "__main__":

random.seed(444)

r1, r2, r3 = asyncio.run(main())

print()

print(f"r1: {r1}, r2: {r2}, r3: {r3}")

The colorized output says a lot more than I can and gives you a sense for how this script is carried out:

This program uses one main coroutine, makerandom(), and runs it concurrently across 3 different inputs. Most programs will contain small, modular coroutines and one wrapper function that serves to chain each of the smaller coroutines together. main() is then used to gather tasks (futures) by mapping the central coroutine across some iterable or pool.

In this miniature example, the pool is range(3). In a fuller example presented later, it is a set of URLs that need to be requested, parsed, and processed concurrently, and main() encapsulates that entire routine for each URL.

While “making random integers” (which is CPU-bound more than anything) is maybe not the greatest choice as a candidate for asyncio, it’s the presence of asyncio.sleep() in the example that is designed to mimic an IO-bound process where there is uncertain wait time involved. For example, the asyncio.sleep() call might represent sending and receiving not-so-random integers between two clients in a message application.

Async IO Design Patterns

Async IO comes with its own set of possible script designs, which you’ll get introduced to in this section.

Chaining Coroutines

A key feature of coroutines is that they can be chained together. (Remember, a coroutine object is awaitable, so another coroutine can await it.) This allows you to break programs into smaller, manageable, recyclable coroutines:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# chained.py

import asyncio

import random

import time

async def part1(n: int) -> str:

i = random.randint(0, 10)

print(f"part1({n}) sleeping for {i} seconds.")

await asyncio.sleep(i)

result = f"result{n}-1"

print(f"Returning part1({n}) == {result}.")

return result

async def part2(n: int, arg: str) -> str:

i = random.randint(0, 10)

print(f"part2{n, arg} sleeping for {i} seconds.")

await asyncio.sleep(i)

result = f"result{n}-2 derived from {arg}"

print(f"Returning part2{n, arg} == {result}.")

return result

async def chain(n: int) -> None:

start = time.perf_counter()

p1 = await part1(n)

p2 = await part2(n, p1)

end = time.perf_counter() - start

print(f"-->Chained result{n} => {p2} (took {end:0.2f} seconds).")

async def main(*args):

await asyncio.gather(*(chain(n) for n in args))

if __name__ == "__main__":

import sys

random.seed(444)

args = [1, 2, 3] if len(sys.argv) == 1 else map(int, sys.argv[1:])

start = time.perf_counter()

asyncio.run(main(*args))

end = time.perf_counter() - start

print(f"Program finished in {end:0.2f} seconds.")

Pay careful attention to the output, where part1() sleeps for a variable amount of time, and part2() begins working with the results as they become available:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

$ python3 chained.py 9 6 3

part1(9) sleeping for 4 seconds.

part1(6) sleeping for 4 seconds.

part1(3) sleeping for 0 seconds.

Returning part1(3) == result3-1.

part2(3, 'result3-1') sleeping for 4 seconds.

Returning part1(9) == result9-1.

part2(9, 'result9-1') sleeping for 7 seconds.

Returning part1(6) == result6-1.

part2(6, 'result6-1') sleeping for 4 seconds.

Returning part2(3, 'result3-1') == result3-2 derived from result3-1.

-->Chained result3 => result3-2 derived from result3-1 (took 4.00 seconds).

Returning part2(6, 'result6-1') == result6-2 derived from result6-1.

-->Chained result6 => result6-2 derived from result6-1 (took 8.01 seconds).

Returning part2(9, 'result9-1') == result9-2 derived from result9-1.

-->Chained result9 => result9-2 derived from result9-1 (took 11.01 seconds).

Program finished in 11.01 seconds.

In this setup, the runtime of main() will be equal to the maximum runtime of the tasks that it gathers together and schedules.

Using a Queue

The asyncio package provides queue classes that are designed to be similar to classes of the queue module. In our examples so far, we haven’t really had a need for a queue structure. In chained.py, each task (future) is composed of a set of coroutines that explicitly await each other and pass through a single input per chain.

There is an alternative structure that can also work with async IO: a number of producers, which are not associated with each other, add items to a queue. Each producer may add multiple items to the queue at staggered, random, unannounced times. A group of consumers pull items from the queue as they show up, greedily and without waiting for any other signal.

In this design, there is no chaining of any individual consumer to a producer. The consumers don’t know the number of producers, or even the cumulative number of items that will be added to the queue, in advance.

It takes an individual producer or consumer a variable amount of time to put and extract items from the queue, respectively. The queue serves as a throughput that can communicate with the producers and consumers without them talking to each other directly.

Note: While queues are often used in threaded programs because of the thread-safety of

queue.Queue(), you shouldn’t need to concern yourself with thread safety when it comes to async IO. (The exception is when you’re combining the two, but that isn’t done in this tutorial.)One use-case for queues (as is the case here) is for the queue to act as a transmitter for producers and consumers that aren’t otherwise directly chained or associated with each other.

The synchronous version of this program would look pretty dismal: a group of blocking producers serially add items to the queue, one producer at a time. Only after all producers are done can the queue be processed, by one consumer at a time processing item-by-item. There is a ton of latency in this design. Items may sit idly in the queue rather than be picked up and processed immediately.

An asynchronous version, asyncq.py, is below. The challenging part of this workflow is that there needs to be a signal to the consumers that production is done. Otherwise, await q.get() will hang indefinitely, because the queue will have been fully processed, but consumers won’t have any idea that production is complete.

(Big thanks for some help from a StackOverflow user for helping to straighten out main(): the key is to await q.join(), which blocks until all items in the queue have been received and processed, and then to cancel the consumer tasks, which would otherwise hang up and wait endlessly for additional queue items to appear.)

Here is the full script:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# asyncq.py

import asyncio

import itertools as it

import os

import random

import time

async def makeitem(size: int = 5) -> str:

return os.urandom(size).hex()

async def randsleep(caller=None) -> None:

i = random.randint(0, 10)

if caller:

print(f"{caller} sleeping for {i} seconds.")

await asyncio.sleep(i)

async def produce(name: int, q: asyncio.Queue) -> None:

n = random.randint(0, 10)

for _ in it.repeat(None, n): # Synchronous loop for each single producer

await randsleep(caller=f"Producer {name}")

i = await makeitem()

t = time.perf_counter()

await q.put((i, t))

print(f"Producer {name} added <{i}> to queue.")

async def consume(name: int, q: asyncio.Queue) -> None:

while True:

await randsleep(caller=f"Consumer {name}")

i, t = await q.get()

now = time.perf_counter()

print(f"Consumer {name} got element <{i}>"

f" in {now-t:0.5f} seconds.")

q.task_done()

async def main(nprod: int, ncon: int):

q = asyncio.Queue()

producers = [asyncio.create_task(produce(n, q)) for n in range(nprod)]

consumers = [asyncio.create_task(consume(n, q)) for n in range(ncon)]

await asyncio.gather(*producers)

await q.join() # Implicitly awaits consumers, too

for c in consumers:

c.cancel()

if __name__ == "__main__":

import argparse

random.seed(444)

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument("-p", "--nprod", type=int, default=5)

parser.add_argument("-c", "--ncon", type=int, default=10)

ns = parser.parse_args()

start = time.perf_counter()

asyncio.run(main(**ns.__dict__))

elapsed = time.perf_counter() - start

print(f"Program completed in {elapsed:0.5f} seconds.")

The first few coroutines are helper functions that return a random string, a fractional-second performance counter, and a random integer. A producer puts anywhere from 1 to 5 items into the queue. Each item is a tuple of (i, t) where i is a random string and t is the time at which the producer attempts to put the tuple into the queue.

When a consumer pulls an item out, it simply calculates the elapsed time that the item sat in the queue using the timestamp that the item was put in with.

Keep in mind that asyncio.sleep() is used to mimic some other, more complex coroutine that would eat up time and block all other execution if it were a regular blocking function.

Here is a test run with two producers and five consumers:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

$ python3 asyncq.py -p 2 -c 5

Producer 0 sleeping for 3 seconds.

Producer 1 sleeping for 3 seconds.

Consumer 0 sleeping for 4 seconds.

Consumer 1 sleeping for 3 seconds.

Consumer 2 sleeping for 3 seconds.

Consumer 3 sleeping for 5 seconds.

Consumer 4 sleeping for 4 seconds.

Producer 0 added <377b1e8f82> to queue.

Producer 0 sleeping for 5 seconds.

Producer 1 added <413b8802f8> to queue.

Consumer 1 got element <377b1e8f82> in 0.00013 seconds.

Consumer 1 sleeping for 3 seconds.

Consumer 2 got element <413b8802f8> in 0.00009 seconds.

Consumer 2 sleeping for 4 seconds.

Producer 0 added <06c055b3ab> to queue.

Producer 0 sleeping for 1 seconds.

Consumer 0 got element <06c055b3ab> in 0.00021 seconds.

Consumer 0 sleeping for 4 seconds.

Producer 0 added <17a8613276> to queue.

Consumer 4 got element <17a8613276> in 0.00022 seconds.

Consumer 4 sleeping for 5 seconds.

Program completed in 9.00954 seconds.

In this case, the items process in fractions of a second. A delay can be due to two reasons:

- Standard, largely unavoidable overhead

- Situations where all consumers are sleeping when an item appears in the queue

With regards to the second reason, luckily, it is perfectly normal to scale to hundreds or thousands of consumers. You should have no problem with python3 asyncq.py -p 5 -c 100. The point here is that, theoretically, you could have different users on different systems controlling the management of producers and consumers, with the queue serving as the central throughput.

So far, you’ve been thrown right into the fire and seen three related examples of asyncio calling coroutines defined with async and await. If you’re not completely following or just want to get deeper into the mechanics of how modern coroutines came to be in Python, you’ll start from square one with the next section.

Async IO’s Roots in Generators

Earlier, you saw an example of the old-style generator-based coroutines, which have been outdated by more explicit native coroutines. The example is worth re-showing with a small tweak:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

import asyncio

@asyncio.coroutine

def py34_coro():

"""Generator-based coroutine"""

# No need to build these yourself, but be aware of what they are

s = yield from stuff()

return s

async def py35_coro():

"""Native coroutine, modern syntax"""

s = await stuff()

return s

async def stuff():

return 0x10, 0x20, 0x30

As an experiment, what happens if you call py34_coro() or py35_coro() on its own, without await, or without any calls to asyncio.run() or other asyncio “porcelain” functions? Calling a coroutine in isolation returns a coroutine object:

>>> py35_coro()

<coroutine object py35_coro at 0x10126dcc8>

This isn’t very interesting on its surface. The result of calling a coroutine on its own is an awaitable coroutine object.

Time for a quiz: what other feature of Python looks like this? (What feature of Python doesn’t actually “do much” when it’s called on its own?)

Hopefully you’re thinking of generators as an answer to this question, because coroutines are enhanced generators under the hood. The behavior is similar in this regard:

>>> def gen():

... yield 0x10, 0x20, 0x30

...

>>> g = gen()

>>> g # Nothing much happens - need to iterate with `.__next__()`

<generator object gen at 0x1012705e8>

>>> next(g)

(16, 32, 48)

Generator functions are, as it so happens, the foundation of async IO (regardless of whether you declare coroutines with async def rather than the older @asyncio.coroutine wrapper). Technically, await is more closely analogous to yield from than it is to yield. (But remember that yield from x() is just syntactic sugar to replace for i in x(): yield i.)

One critical feature of generators as it pertains to async IO is that they can effectively be stopped and restarted at will. For example, you can break out of iterating over a generator object and then resume iteration on the remaining values later. When a generator function reaches yield, it yields that value, but then it sits idle until it is told to yield its subsequent value.

This can be fleshed out through an example:

>>> from itertools import cycle

>>> def endless():

... """Yields 9, 8, 7, 6, 9, 8, 7, 6, ... forever"""

... yield from cycle((9, 8, 7, 6))

>>> e = endless()

>>> total = 0

>>> for i in e:

... if total < 30:

... print(i, end=" ")

... total += i

... else:

... print()

... # Pause execution. We can resume later.

... break

9 8 7 6 9 8 7 6 9 8 7 6 9 8

>>> # Resume

>>> next(e), next(e), next(e)

(6, 9, 8)

The await keyword behaves similarly, marking a break point at which the coroutine suspends itself and lets other coroutines work. “Suspended,” in this case, means a coroutine that has temporarily ceded control but not totally exited or finished. Keep in mind that yield, and by extension yield from and await, mark a break point in a generator’s execution.

This is the fundamental difference between functions and generators. A function is all-or-nothing. Once it starts, it won’t stop until it hits a return, then pushes that value to the caller (the function that calls it). A generator, on the other hand, pauses each time it hits a yield and goes no further. Not only can it push this value to calling stack, but it can keep a hold of its local variables when you resume it by calling next() on it.

There’s a second and lesser-known feature of generators that also matters. You can send a value into a generator as well through its .send() method. This allows generators (and coroutines) to call (await) each other without blocking. I won’t get any further into the nuts and bolts of this feature, because it matters mainly for the implementation of coroutines behind the scenes, but you shouldn’t ever really need to use it directly yourself.

If you’re interested in exploring more, you can start at PEP 342, where coroutines were formally introduced. Brett Cannon’s How the Heck Does Async-Await Work in Python is also a good read, as is the PYMOTW writeup on asyncio. Lastly, there’s David Beazley’s Curious Course on Coroutines and Concurrency, which dives deep into the mechanism by which coroutines run.

Let’s try to condense all of the above articles into a few sentences: there is a particularly unconventional mechanism by which these coroutines actually get run. Their result is an attribute of the exception object that gets thrown when their .send() method is called. There’s some more wonky detail to all of this, but it probably won’t help you use this part of the language in practice, so let’s move on for now.

To tie things together, here are some key points on the topic of coroutines as generators:

- Coroutines are repurposed generators that take advantage of the peculiarities of generator methods.

- Old generator-based coroutines use

yield fromto wait for a coroutine result. Modern Python syntax in native coroutines simply replacesyield fromwithawaitas the means of waiting on a coroutine result. Theawaitis analogous toyield from, and it often helps to think of it as such. - The use of

awaitis a signal that marks a break point. It lets a coroutine temporarily suspend execution and permits the program to come back to it later.

Other Features: async for and Async Generators + Comprehensions

Along with plain async/await, Python also enables async for to iterate over an asynchronous iterator. The purpose of an asynchronous iterator is for it to be able to call asynchronous code at each stage when it is iterated over.

A natural extension of this concept is an asynchronous generator. Recall that you can use await, return, or yield in a native coroutine. Using yield within a coroutine became possible in Python 3.6 (via PEP 525), which introduced asynchronous generators with the purpose of allowing await and yield to be used in the same coroutine function body:

>>> async def mygen(u: int = 10):

... """Yield powers of 2."""

... i = 0

... while i < u:

... yield 2 ** i

... i += 1

... await asyncio.sleep(0.1)

Last but not least, Python enables asynchronous comprehension with async for. Like its synchronous cousin, this is largely syntactic sugar:

>>> async def main():

... # This does *not* introduce concurrent execution

... # It is meant to show syntax only

... g = [i async for i in mygen()]

... f = [j async for j in mygen() if not (j // 3 % 5)]

... return g, f

...

>>> g, f = asyncio.run(main())

>>> g

[1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512]

>>> f

[1, 2, 16, 32, 256, 512]

This is a crucial distinction: neither asynchronous generators nor comprehensions make the iteration concurrent. All that they do is provide the look-and-feel of their synchronous counterparts, but with the ability for the loop in question to give up control to the event loop for some other coroutine to run.

In other words, asynchronous iterators and asynchronous generators are not designed to concurrently map some function over a sequence or iterator. They’re merely designed to let the enclosing coroutine allow other tasks to take their turn. The async for and async with statements are only needed to the extent that using plain for or with would “break” the nature of await in the coroutine. This distinction between asynchronicity and concurrency is a key one to grasp.

The Event Loop and asyncio.run()

You can think of an event loop as something like a while True loop that monitors coroutines, taking feedback on what’s idle, and looking around for things that can be executed in the meantime. It is able to wake up an idle coroutine when whatever that coroutine is waiting on becomes available.

Thus far, the entire management of the event loop has been implicitly handled by one function call:

1

asyncio.run(main()) # Python 3.7+

asyncio.run(), introduced in Python 3.7, is responsible for getting the event loop, running tasks until they are marked as complete, and then closing the event loop.

There’s a more long-winded way of managing the asyncio event loop, with get_event_loop(). The typical pattern looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

try:

loop.run_until_complete(main())

finally:

loop.close()

You’ll probably see loop.get_event_loop() floating around in older examples, but unless you have a specific need to fine-tune control over the event loop management, asyncio.run() should be sufficient for most programs.

If you do need to interact with the event loop within a Python program, loop is a good-old-fashioned Python object that supports introspection with loop.is_running() and loop.is_closed(). You can manipulate it if you need to get more fine-tuned control, such as in scheduling a callback by passing the loop as an argument.

What is more crucial is understanding a bit beneath the surface about the mechanics of the event loop. Here are a few points worth stressing about the event loop.

#1: Coroutines don’t do much on their own until they are tied to the event loop.

You saw this point before in the explanation on generators, but it’s worth restating. If you have a main coroutine that awaits others, simply calling it in isolation has little effect:

>>> import asyncio

>>> async def main():

... print("Hello ...")

... await asyncio.sleep(1)

... print("World!")

>>> routine = main()

>>> routine

<coroutine object main at 0x1027a6150>

Remember to use asyncio.run() to actually force execution by scheduling the main() coroutine (future object) for execution on the event loop:

>>> asyncio.run(routine)

Hello ...

World!

(Other coroutines can be executed with await. It is typical to wrap just main() in asyncio.run(), and chained coroutines with await will be called from there.)

#2: By default, an async IO event loop runs in a single thread and on a single CPU core. Usually, running one single-threaded event loop in one CPU core is more than sufficient. It is also possible to run event loops across multiple cores. Check out this talk by John Reese for more, and be warned that your laptop may spontaneously combust.

#3. Event loops are pluggable. That is, you could, if you really wanted, write your own event loop implementation and have it run tasks just the same. This is wonderfully demonstrated in the uvloop package, which is an implementation of the event loop in Cython.

That is what is meant by the term “pluggable event loop”: you can use any working implementation of an event loop, unrelated to the structure of the coroutines themselves. The asyncio package itself ships with two different event loop implementations, with the default being based on the selectors module. (The second implementation is built for Windows only.)

A Full Program: Asynchronous Requests

You’ve made it this far, and now it’s time for the fun and painless part. In this section, you’ll build a web-scraping URL collector, areq.py, using aiohttp, a blazingly fast async HTTP client/server framework. (We just need the client part.) Such a tool could be used to map connections between a cluster of sites, with the links forming a directed graph.

Note: You may be wondering why Python’s

requestspackage isn’t compatible with async IO.requestsis built on top ofurllib3, which in turn uses Python’shttpandsocketmodules.By default, socket operations are blocking. This means that Python won’t like

await requests.get(url)because.get()is not awaitable. In contrast, almost everything inaiohttpis an awaitable coroutine, such assession.request()andresponse.text(). It’s a great package otherwise, but you’re doing yourself a disservice by usingrequestsin asynchronous code.

The high-level program structure will look like this:

- Read a sequence of URLs from a local file,

urls.txt. - Send GET requests for the URLs and decode the resulting content. If this fails, stop there for a URL.

- Search for the URLs within

hreftags in the HTML of the responses. - Write the results to

foundurls.txt. - Do all of the above as asynchronously and concurrently as possible. (Use

aiohttpfor the requests, andaiofilesfor the file-appends. These are two primary examples of IO that are well-suited for the async IO model.)

Here are the contents of urls.txt. It’s not huge, and contains mostly highly trafficked sites:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

$ cat urls.txt

https://regex101.com/

https://docs.python.org/3/this-url-will-404.html

https://www.nytimes.com/guides/

https://www.mediamatters.org/

https://1.1.1.1/

https://www.politico.com/tipsheets/morning-money

https://www.bloomberg.com/markets/economics

https://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2616.txt

The second URL in the list should return a 404 response, which you’ll need to handle gracefully. If you’re running an expanded version of this program, you’ll probably need to deal with much hairier problems than this, such a server disconnections and endless redirects.

The requests themselves should be made using a single session, to take advantage of reusage of the session’s internal connection pool.

Let’s take a look at the full program. We’ll walk through things step-by-step after:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# areq.py

"""Asynchronously get links embedded in multiple pages' HMTL."""

import asyncio

import logging

import re

import sys

from typing import IO

import urllib.error

import urllib.parse

import aiofiles

import aiohttp

from aiohttp import ClientSession

logging.basicConfig(

format="%(asctime)s %(levelname)s:%(name)s: %(message)s",

level=logging.DEBUG,

datefmt="%H:%M:%S",

stream=sys.stderr,

)

logger = logging.getLogger("areq")

logging.getLogger("chardet.charsetprober").disabled = True

HREF_RE = re.compile(r'href="(.*?)"')

async def fetch_html(url: str, session: ClientSession, **kwargs) -> str:

"""GET request wrapper to fetch page HTML.

kwargs are passed to `session.request()`.

"""

resp = await session.request(method="GET", url=url, **kwargs)

resp.raise_for_status()

logger.info("Got response [%s] for URL: %s", resp.status, url)

html = await resp.text()

return html

async def parse(url: str, session: ClientSession, **kwargs) -> set:

"""Find HREFs in the HTML of `url`."""

found = set()

try:

html = await fetch_html(url=url, session=session, **kwargs)

except (

aiohttp.ClientError,

aiohttp.http_exceptions.HttpProcessingError,

) as e:

logger.error(

"aiohttp exception for %s [%s]: %s",

url,

getattr(e, "status", None),

getattr(e, "message", None),

)

return found

except Exception as e:

logger.exception(

"Non-aiohttp exception occured: %s", getattr(e, "__dict__", {})

)

return found

else:

for link in HREF_RE.findall(html):

try:

abslink = urllib.parse.urljoin(url, link)

except (urllib.error.URLError, ValueError):

logger.exception("Error parsing URL: %s", link)

pass

else:

found.add(abslink)

logger.info("Found %d links for %s", len(found), url)

return found

async def write_one(file: IO, url: str, **kwargs) -> None:

"""Write the found HREFs from `url` to `file`."""

res = await parse(url=url, **kwargs)

if not res:

return None

async with aiofiles.open(file, "a") as f:

for p in res:

await f.write(f"{url}\t{p}\n")

logger.info("Wrote results for source URL: %s", url)

async def bulk_crawl_and_write(file: IO, urls: set, **kwargs) -> None:

"""Crawl & write concurrently to `file` for multiple `urls`."""

async with ClientSession() as session:

tasks = []

for url in urls:

tasks.append(

write_one(file=file, url=url, session=session, **kwargs)

)

await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

if __name__ == "__main__":

import pathlib

import sys

assert sys.version_info >= (3, 7), "Script requires Python 3.7+."

here = pathlib.Path(__file__).parent

with open(here.joinpath("urls.txt")) as infile:

urls = set(map(str.strip, infile))

outpath = here.joinpath("foundurls.txt")

with open(outpath, "w") as outfile:

outfile.write("source_url\tparsed_url\n")

asyncio.run(bulk_crawl_and_write(file=outpath, urls=urls))

This script is longer than our initial toy programs, so let’s break it down.

The constant HREF_RE is a regular expression to extract what we’re ultimately searching for, href tags within HTML:

>>> HREF_RE.search('Go to <a href="https://realpython.com/">Real Python</a>')

<re.Match object; span=(15, 45), match='href="https://realpython.com/"'>

The coroutine fetch_html() is a wrapper around a GET request to make the request and decode the resulting page HTML. It makes the request, awaits the response, and raises right away in the case of a non-200 status:

resp = await session.request(method="GET", url=url, **kwargs)

resp.raise_for_status()

If the status is okay, fetch_html() returns the page HTML (a str). Notably, there is no exception handling done in this function. The logic is to propagate that exception to the caller and let it be handled there:

html = await resp.text()

We await session.request() and resp.text() because they’re awaitable coroutines. The request/response cycle would otherwise be the long-tailed, time-hogging portion of the application, but with async IO, fetch_html() lets the event loop work on other readily available jobs such as parsing and writing URLs that have already been fetched.

Next in the chain of coroutines comes parse(), which waits on fetch_html() for a given URL, and then extracts all of the href tags from that page’s HTML, making sure that each is valid and formatting it as an absolute path.

Admittedly, the second portion of parse() is blocking, but it consists of a quick regex match and ensuring that the links discovered are made into absolute paths.

In this specific case, this synchronous code should be quick and inconspicuous. But just remember that any line within a given coroutine will block other coroutines unless that line uses yield, await, or return. If the parsing was a more intensive process, you might want to consider running this portion in its own process with loop.run_in_executor().

Next, the coroutine write() takes a file object and a single URL, and waits on parse() to return a set of the parsed URLs, writing each to the file asynchronously along with its source URL through use of aiofiles, a package for async file IO.

Lastly, bulk_crawl_and_write() serves as the main entry point into the script’s chain of coroutines. It uses a single session, and a task is created for each URL that is ultimately read from urls.txt.

Here are a few additional points that deserve mention:

- The default

ClientSessionhas an adapter with a maximum of 100 open connections. To change that, pass an instance ofasyncio.connector.TCPConnectortoClientSession. You can also specify limits on a per-host basis. - You can specify max timeouts for both the session as a whole and for individual requests.

- This script also uses

async with, which works with an asynchronous context manager. I haven’t devoted a whole section to this concept because the transition from synchronous to asynchronous context managers is fairly straightforward. The latter has to define.__aenter__()and.__aexit__()rather than.__exit__()and.__enter__(). As you might expect,async withcan only be used inside a coroutine function declared withasync def.

If you’d like to explore a bit more, the companion files for this tutorial up at GitHub have comments and docstrings attached as well.

Here’s the execution in all of its glory, as areq.py gets, parses, and saves results for 9 URLs in under a second:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

$ python3 areq.py

21:33:22 DEBUG:asyncio: Using selector: KqueueSelector

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Got response [200] for URL: https://www.mediamatters.org/

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Found 115 links for https://www.mediamatters.org/

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Got response [200] for URL: https://www.nytimes.com/guides/

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Got response [200] for URL: https://www.politico.com/tipsheets/morning-money

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Got response [200] for URL: https://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2616.txt

21:33:22 ERROR:areq: aiohttp exception for https://docs.python.org/3/this-url-will-404.html [404]: Not Found

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Found 120 links for https://www.nytimes.com/guides/

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Found 143 links for https://www.politico.com/tipsheets/morning-money

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Wrote results for source URL: https://www.mediamatters.org/

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Found 0 links for https://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2616.txt

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Got response [200] for URL: https://1.1.1.1/

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Wrote results for source URL: https://www.nytimes.com/guides/

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Wrote results for source URL: https://www.politico.com/tipsheets/morning-money

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Got response [200] for URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/markets/economics

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Found 3 links for https://www.bloomberg.com/markets/economics

21:33:22 INFO:areq: Wrote results for source URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/markets/economics

21:33:23 INFO:areq: Found 36 links for https://1.1.1.1/

21:33:23 INFO:areq: Got response [200] for URL: https://regex101.com/

21:33:23 INFO:areq: Found 23 links for https://regex101.com/

21:33:23 INFO:areq: Wrote results for source URL: https://regex101.com/

21:33:23 INFO:areq: Wrote results for source URL: https://1.1.1.1/

That’s not too shabby! As a sanity check, you can check the line-count on the output. In my case, it’s 626, though keep in mind this may fluctuate:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

$ wc -l foundurls.txt

626 foundurls.txt

$ head -n 3 foundurls.txt

source_url parsed_url

https://www.bloomberg.com/markets/economics https://www.bloomberg.com/feedback

https://www.bloomberg.com/markets/economics https://www.bloomberg.com/notices/tos

Next Steps: If you’d like to up the ante, make this webcrawler recursive. You can use

aio-redisto keep track of which URLs have been crawled within the tree to avoid requesting them twice, and connect links with Python’snetworkxlibrary.Remember to be nice. Sending 1000 concurrent requests to a small, unsuspecting website is bad, bad, bad. There are ways to limit how many concurrent requests you’re making in one batch, such as in using the sempahore objects of

asyncioor using a pattern like this one. If you don’t heed this warning, you may get a massive batch ofTimeoutErrorexceptions and only end up hurting your own program.

Async IO in Context

Now that you’ve seen a healthy dose of code, let’s step back for a minute and consider when async IO is an ideal option and how you can make the comparison to arrive at that conclusion or otherwise choose a different model of concurrency.

When and Why Is Async IO the Right Choice?

This tutorial is no place for an extended treatise on async IO versus threading versus multiprocessing. However, it’s useful to have an idea of when async IO is probably the best candidate of the three.

The battle over async IO versus multiprocessing is not really a battle at all. In fact, they can be used in concert. If you have multiple, fairly uniform CPU-bound tasks (a great example is a grid search in libraries such as scikit-learn or keras), multiprocessing should be an obvious choice.

Simply putting async before every function is a bad idea if all of the functions use blocking calls. (This can actually slow down your code.) But as mentioned previously, there are places where async IO and multiprocessing can live in harmony.

The contest between async IO and threading is a little bit more direct. I mentioned in the introduction that “threading is hard.” The full story is that, even in cases where threading seems easy to implement, it can still lead to infamous impossible-to-trace bugs due to race conditions and memory usage, among other things.

Threading also tends to scale less elegantly than async IO, because threads are a system resource with a finite availability. Creating thousands of threads will fail on many machines, and I don’t recommend trying it in the first place. Creating thousands of async IO tasks is completely feasible.

Async IO shines when you have multiple IO-bound tasks where the tasks would otherwise be dominated by blocking IO-bound wait time, such as:- Network IO, whether your program is the server or the client side

- Serverless designs, such as a peer-to-peer, multi-user network like a group chatroom

- Read/write operations where you want to mimic a “fire-and-forget” style but worry less about holding a lock on whatever you’re reading and writing to

The biggest reason not to use it is that await only supports a specific set of objects that define a specific set of methods. If you want to do async read operations with a certain DBMS, you’ll need to find not just a Python wrapper for that DBMS, but one that supports the async/await syntax. Coroutines that contain synchronous calls block other coroutines and tasks from running.

For a shortlist of libraries that work with async/await, see the list at the end of this tutorial.

Async IO It Is, but Which One?

This tutorial focuses on async IO, the async/await syntax, and using asyncio for event-loop management and specifying tasks. asyncio certainly isn’t the only async IO library out there. This observation from Nathaniel J. Smith says a lot:

[In] a few years,

asynciomight find itself relegated to becoming one of those stdlib libraries that savvy developers avoid, likeurllib2.…

What I’m arguing, in effect, is that

asynciois a victim of its own success: when it was designed, it used the best approach possible; but since then, work inspired byasyncio– like the addition ofasync/await– has shifted the landscape so that we can do even better, and nowasynciois hamstrung by its earlier commitments. (Source)

To that end, a few big-name alternatives that do what asyncio does, albeit with different APIs and different approaches, are curio and trio. Personally, I think that if you’re building a moderately sized, straightforward program, just using asyncio is plenty sufficient and understandable, and lets you avoid adding yet another large dependency outside of Python’s standard library.

But by all means, check out curio and trio, and you might find that they get the same thing done in a way that’s more intuitive for you as the user. Many of the package-agnostic concepts presented here should permeate to alternative async IO packages as well.

Odds and Ends

In these next few sections, you’ll cover some miscellaneous parts of asyncio and async/await that haven’t fit neatly into the tutorial thus far, but are still important for building and understanding a full program.

Other Top-Level asyncio Functions

In addition to asyncio.run(), you’ve seen a few other package-level functions such as asyncio.create_task() and asyncio.gather().

You can use create_task() to schedule the execution of a coroutine object, followed by asyncio.run():

>>> import asyncio

>>> async def coro(seq) -> list:

... """'IO' wait time is proportional to the max element."""

... await asyncio.sleep(max(seq))

... return list(reversed(seq))

...

>>> async def main():

... # This is a bit redundant in the case of one task

... # We could use `await coro([3, 2, 1])` on its own

... t = asyncio.create_task(coro([3, 2, 1])) # Python 3.7+

... await t

... print(f't: type {type(t)}')

... print(f't done: {t.done()}')

...

>>> t = asyncio.run(main())

t: type <class '_asyncio.Task'>

t done: True

There’s a subtlety to this pattern: if you don’t await t within main(), it may finish before main() itself signals that it is complete. Because asyncio.run(main()) calls loop.run_until_complete(main()), the event loop is only concerned (without await t present) that main() is done, not that the tasks that get created within main() are done. Without await t, the loop’s other tasks will be cancelled, possibly before they are completed. If you need to get a list of currently pending tasks, you can use asyncio.Task.all_tasks().

Note: asyncio.create_task() was introduced in Python 3.7. In Python 3.6 or lower, use asyncio.ensure_future() in place of create_task().

Separately, there’s asyncio.gather(). While it doesn’t do anything tremendously special, gather() is meant to neatly put a collection of coroutines (futures) into a single future. As a result, it returns a single future object, and, if you await asyncio.gather() and specify multiple tasks or coroutines, you’re waiting for all of them to be completed. (This somewhat parallels queue.join() from our earlier example.) The result of gather() will be a list of the results across the inputs:

>>> import time

>>> async def main():

... t = asyncio.create_task(coro([3, 2, 1]))

... t2 = asyncio.create_task(coro([10, 5, 0])) # Python 3.7+

... print('Start:', time.strftime('%X'))

... a = await asyncio.gather(t, t2)

... print('End:', time.strftime('%X')) # Should be 10 seconds

... print(f'Both tasks done: {all((t.done(), t2.done()))}')

... return a

...

>>> a = asyncio.run(main())

Start: 16:20:11

End: 16:20:21

Both tasks done: True

>>> a

[[1, 2, 3], [0, 5, 10]]

You probably noticed that gather() waits on the entire result set of the Futures or coroutines that you pass it. Alternatively, you can loop over asyncio.as_completed() to get tasks as they are completed, in the order of completion. The function returns an iterator that yields tasks as they finish. Below, the result of coro([3, 2, 1]) will be available before coro([10, 5, 0]) is complete, which is not the case with gather():

>>> async def main():

... t = asyncio.create_task(coro([3, 2, 1]))

... t2 = asyncio.create_task(coro([10, 5, 0]))

... print('Start:', time.strftime('%X'))

... for res in asyncio.as_completed((t, t2)):

... compl = await res

... print(f'res: {compl} completed at {time.strftime("%X")}')

... print('End:', time.strftime('%X'))

... print(f'Both tasks done: {all((t.done(), t2.done()))}')

...

>>> a = asyncio.run(main())

Start: 09:49:07

res: [1, 2, 3] completed at 09:49:10

res: [0, 5, 10] completed at 09:49:17

End: 09:49:17

Both tasks done: True

Lastly, you may also see asyncio.ensure_future(). You should rarely need it, because it’s a lower-level plumbing API and largely replaced by create_task(), which was introduced later.

The Precedence of await

While they behave somewhat similarly, the await keyword has significantly higher precedence than yield. This means that, because it is more tightly bound, there are a number of instances where you’d need parentheses in a yield from statement that are not required in an analogous await statement. For more information, see examples of await expressions from PEP 492.

Conclusion

You’re now equipped to use async/await and the libraries built off of it. Here’s a recap of what you’ve covered:

- Asynchronous IO as a language-agnostic model and a way to effect concurrency by letting coroutines indirectly communicate with each other

- The specifics of Python’s new

asyncandawaitkeywords, used to mark and define coroutines asyncio, the Python package that provides the API to run and manage coroutines

Resources

Python Version Specifics

Async IO in Python has evolved swiftly, and it can be hard to keep track of what came when. Here’s a list of Python minor-version changes and introductions related to asyncio:

- 3.3: The

yield fromexpression allows for generator delegation. - 3.4:

asynciowas introduced in the Python standard library with provisional API status. - 3.5:

asyncandawaitbecame a part of the Python grammar, used to signify and wait on coroutines. They were not yet reserved keywords. (You could still define functions or variables namedasyncandawait.) - 3.6: Asynchronous generators and asynchronous comprehensions were introduced. The API of

asynciowas declared stable rather than provisional. - 3.7:

asyncandawaitbecame reserved keywords. (They cannot be used as identifiers.) They are intended to replace theasyncio.coroutine()decorator.asyncio.run()was introduced to theasynciopackage, among a bunch of other features.

If you want to be safe (and be able to use asyncio.run()), go with Python 3.7 or above to get the full set of features.

Articles

Here’s a curated list of additional resources:

- Real Python: Speed up your Python Program with Concurrency

- Real Python: What is the Python Global Interpreter Lock?

- CPython: The

asynciopackage source - Python docs: Data model > Coroutines

- TalkPython: Async Techniques and Examples in Python

- Brett Cannon: How the Heck Does Async-Await Work in Python 3.5?

- PYMOTW:

asyncio - A. Jesse Jiryu Davis and Guido van Rossum: A Web Crawler With asyncio Coroutines

- Andy Pearce: The State of Python Coroutines:

yield from - Nathaniel J. Smith: Some Thoughts on Asynchronous API Design in a Post-

async/awaitWorld - Armin Ronacher: I don’t understand Python’s Asyncio

- Andy Balaam: series on

asyncio(4 posts) - Stack Overflow: Python

asyncio.semaphoreinasync-awaitfunction - Yeray Diaz:

A few Python What’s New sections explain the motivation behind language changes in more detail:

- What’s New in Python 3.3 (

yield fromand PEP 380) - What’s New in Python 3.6 (PEP 525 & 530)

From David Beazley:

- Generator: Tricks for Systems Programmers

- A Curious Course on Coroutines and Concurrency

- Generators: The Final Frontier

YouTube talks:

- John Reese - Thinking Outside the GIL with AsyncIO and Multiprocessing - PyCon 2018

- Keynote David Beazley - Topics of Interest (Python Asyncio)

- David Beazley - Python Concurrency From the Ground Up: LIVE! - PyCon 2015

- Raymond Hettinger, Keynote on Concurrency, PyBay 2017

- Thinking about Concurrency, Raymond Hettinger, Python core developer

- Miguel Grinberg Asynchronous Python for the Complete Beginner PyCon 2017

- Yury Selivanov asyncawait and asyncio in Python 3 6 and beyond PyCon 2017

- Fear and Awaiting in Async: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the Coroutine Dream

- What Is Async, How Does It Work, and When Should I Use It? (PyCon APAC 2014)

Related PEPs

Libraries That Work With async/await

From aio-libs:

aiohttp: Asynchronous HTTP client/server frameworkaioredis: Async IO Redis supportaiopg: Async IO PostgreSQL supportaiomcache: Async IO memcached clientaiokafka: Async IO Kafka clientaiozmq: Async IO ZeroMQ supportaiojobs: Jobs scheduler for managing background tasksasync_lru: Simple LRU cache for async IO

From magicstack:

From other hosts:

trio: Friendlierasynciointended to showcase a radically simpler designaiofiles: Async file IOasks: Async requests-like http libraryasyncio-redis: Async IO Redis supportaioprocessing: Integratesmultiprocessingmodule withasyncioumongo: Async IO MongoDB clientunsync: Unsynchronizeasyncioaiostream: Likeitertools, but async